Oh, the temptation. You’re already sitting in front of a computer for a virtual event, why not just write out your presentation or speech word-for-word and have it pulled up on screen? Now you can get away with ‘eye contact’ since your camera is… sort of… where you’re looking. And there’s no worrying about hand gestures, or walking and talking. This is amazing!

Hold on.

The problem is, it doesn’t matter if you’re presenting on a stage or through a computer, tablet, cellphone or Jetsons video wristwatch (wait. We’re pretty close to that being a real thing, right?).

The second you start reciting a meticulously crafted script, those words, no matter how poetic, lose value because you lose authenticity. It moves away from a personalized presentation from a subject matter expert and ventures toward something mechanical and cold. Formal prose is the antithesis of casual conversation, and it creates a distance between the speaker and audience – speaking of, don’t even get me started on the problems with lecterns!

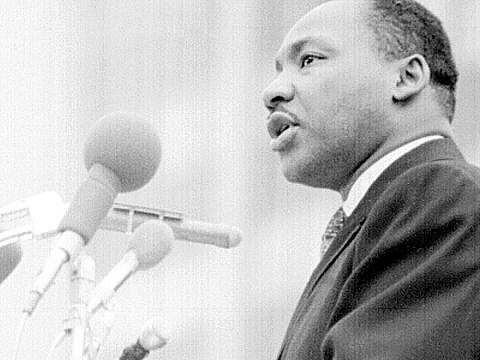

But if that’s the case, why do we feel so moved by famous, historical speeches that are scripted? Like, Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous 1963 ‘I Have a Dream’ speech.

As it would turn out, the text placed on the podium at the Lincoln Memorial that day did not include the four-word refrain that ultimately defined the speech.

As reported by Forbes, the pastor’s speechwriter watched King, nearing the seventh paragraph, “push the text of his prepared remarks to one side of the lectern. He shifted gears in a heartbeat, abandoning whatever final version he’d prepared…he’d given himself over to the spirit of the moment.”

The rest of the speech was largely improvised, including the eternal ‘I Have a Dream’ phrase. Watch the video of that late August day and you’ll see King’s mid-speech abandonment of the script brings his eyes upward and delivers a palpable connection to the masses gathered on the National Mall. The moment instantly became more engaging.

Know, though, that improvised doesn’t mean King came up with the rest of the speech on the fly. “In fact King delivered the now familiar refrain, or at least a version of it, two months earlier at Cobo Hall in Detroit,” Forbes reports.

This speaks to the importance of knowing your content inside and out – one of the eight foundational presenter guidelines from Centrifuge CEO and go-to performance development man, Brian Rivers. It’s his first tip on the list and probably the most obvious. At the time, Rivers approached it from a place of helping determine what kind of content would best captivate and interest the audience. Now, we’ve taken it a step further to bolster our argument for a world without scripts. Having full confidence and expertise in your content allows easy improvisation in an organic and engaging way, just like MLK showed us almost 60 years ago.

Grabbing the audience and smooth ad libbing aren’t the only reasons to know your stuff, though. Chris Hargreaves, an Australian attorney-turned-marketing expert for legal firms sums it up in eight words in his article on the keys to a good presentation for lawyers (yet applicable to any profession). “If you’re an expert… why are you reading?” he asks. It doesn’t take expertise to read, but it does take expertise to know the information. Show it! The audience will be more convinced to believe a speaker when the presentation sounds closer to a natural conversation than a performance.

Combine all of the above and it adds up to Rivers’ fifth tip: choose authenticity over perfection. “When you favor the development of a connection with your audience over a perfectly polished performance, you build an element of trust and relatability that otherwise cannot be achieved.”

Still not sold on chucking the script? Look at TED Talks. Many of them go viral because, well, they’re fantastic! Word on the street is there are 10 Commandments given to the speakers to help them achieve such greatness. Would you really be surprised to learn that number nine is ‘Thou shalt not read thy speech’? “Probably the worst of all public speaking sins,” Collective Hub says of scripting reciting. “If they wanted to be read to, you could’ve just sent them an email with your speech content.”

A human behavior consultancy group even backed up the supposed TED 10 Commandments by polling volunteers who watched hundreds of hours of TED Talks. The findings pointed to five nonverbal patterns seen time and time again in the higher rated TED Talks, including speakers who clearly ad libbed.

Speaking of commandments, we’ll at least play devil’s advocate. Indeed, there are some cons to internalizing a speech and pros to scripting it out. Sims Wyeth gives it to us straight; By scripting, your ideas are laid out clearly, you’ll likely feel more secure and it minimizes rehearsal time. Internalizing a script, Wyeth says, is admittedly hard work and will take significant effort to plant into your memory. You also run the risk of going blank.

Wyeth also provides a slew of upsides to internalizing and downsides to scripting – with noticeably more benefits to ditching the script than the opposite. One pro he provides that we haven’t touched on yet, is the audience gets to see a speaker think on their feet. It demonstrates courage and confidence, which can translate into adrenaline and high energy felt by the attendees.

So how do you do it? The best starting point is bullet points. Jot down key topics, numbers, information, etc. that you need to say. Then, set a few bullets aside for what you’d like to say in conjunction with your pertinent content, like anecdotes. And finally, designate a few things to share if you have the time – the stuff you can live without, if need be. With ample practice, which is a must, very few words can launch you into your zone.

Mapping out the ‘story’ you’re going to share is another fantastic piece of advice for those ready to pull the plug on scripting. We’re big fans of storytelling at Centrifuge Media, which is taking the audience on a journey with your content. It should include personal, emotion-evoking anecdotes, making the listener feel more connected to you and therefore more interested in what you have to say. Good storytelling still ticks off the five Ws: who, what, when, where, why (and how), but it feels less like a news report and more like a good book. To become a great storyteller, sketch out a rough roadmap of your five Ws and determine where your anecdotes can fit in organically. And, of course, practice!

In time, any script lover can become a scriptless master. It just takes a change in mindset, a healthy dose of confidence and enough practice. You got this!